By Sean Johnson

The Executioner Tracklist

1. The Walnut Tree Waves In The Wind

2. Woman, You Are Pregnant (Woman One)

3. The Eternal Soldier - Help Him!

4. Field Recording

5. In The Spring Night, Hoarfrost Falls

6. Child’s Play

7. The Marble Picture

8. Addamaria

9. Compiege Soldier

10. Confessions Of A Hallow

11. The Execution

12. The Next Moment In History Belongs To Us

Den Røde Skov Tracklist

1. Introduction

2. Fanefjord

3. The Mirror

4. The Red Forest

5. The Red Door

6. The Cliff

7. The Blue Room

8. Landscape With Wolves Bed

9. Wolf Song

10. Durand’s Flute

11. The End (Glass Music)

The UK-based Penultimate Press (run by Mark Harwood aka Astor) continues their ongoing retrospective/excavation of the neglected Danish Fluxus-aligned composer Henning Christiansen with two new archival releases sharing the distinction of being scores for films directed by his partner and collaborator Ursula Reuter Christiansen. The label’s back-catalogue—home to such luminaries as Graham Lambkin, Księżyc, Étant Donnés, and Áine O'Dwyer—points to a constellation of outré artists united, however tenuously, by an aesthetic departing from Christiansen himself: a sort of rustic, homespun, off-kilter style enmeshed within the soundscape of local folklore and ecology. It is therefore appropriate that Penultimate is taking up the task of bringing attention to this underappreciated composer and subsequently filling in a historical gap between the now-canonized Fluxus sound art of Nam June Paik et al. and the legion contemporary artists in its trajectory.

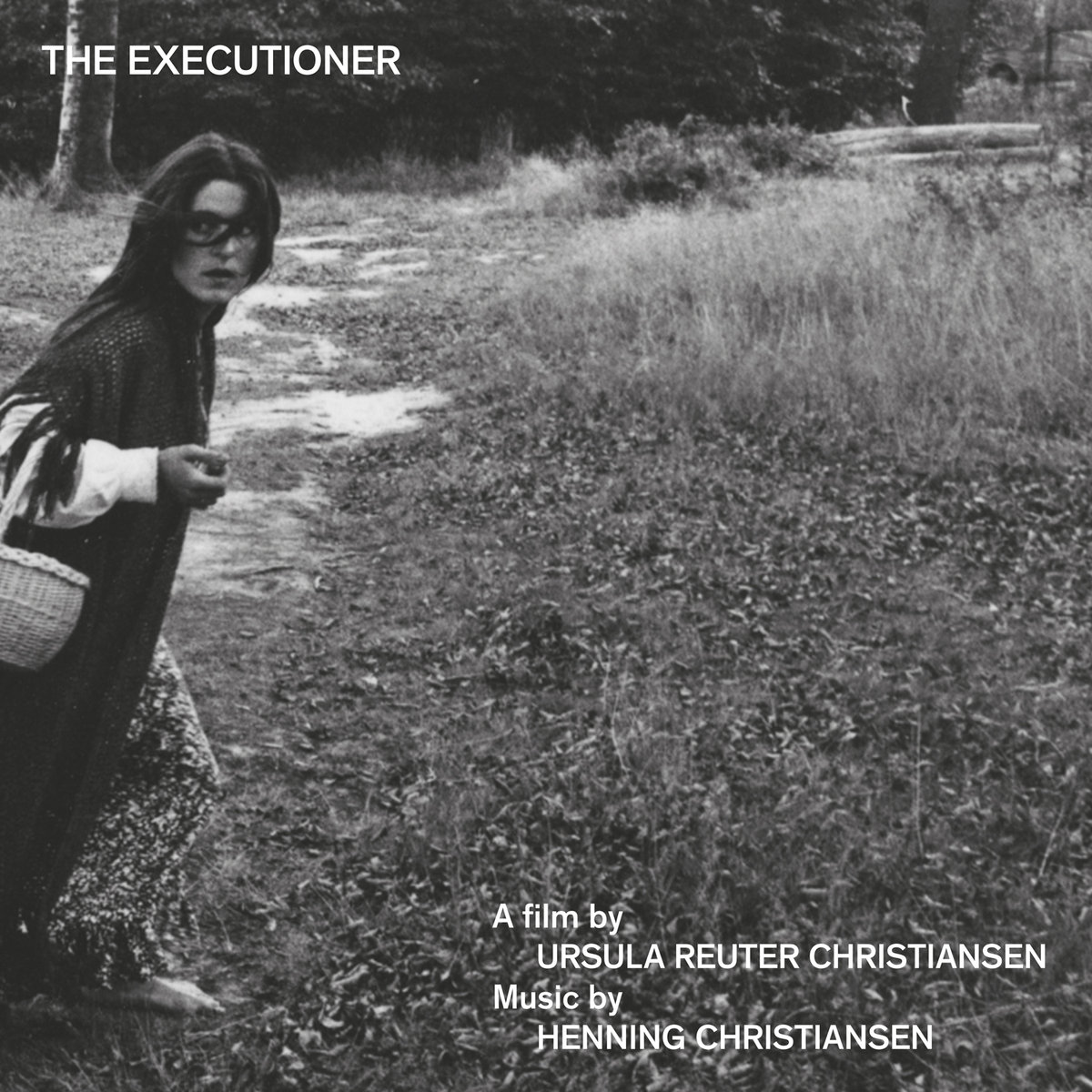

The Executioner (Skarpretteren), Ursula’s debut film from 1971, is a confrontational work questioning the role of the feminine. A series of allegorical tableaux depicts Ursula in the form of mythic maternal Woman, who abandons her fixed positions—mother, healer, lover—for the death-drive of the red-cloaked executioner, to whom she surrenders her life. Though regretfully unavailable for this reviewer to watch, the promotional stills suggest a forlorn tone redolent of fellow Dane Carl Th. Dreyer’s haunting Ordet and the Ingmar Bergman of The Virgin Spring. (The film’s setting, the Danish island of Møn, also bears a close resemblance to the Fårö island synonymous with Bergman’s filmography). One may also surmise from its subject matter that it serves as a notable contribution to the interrogation of naturalized gender mounted in 1970s feminist cinema by such films as Valie Export’s Unsichtbare Gegner (Invisible Adversaries).

The score is an appropriately stark set of Wagnerian late-Romantic vocal chamber music progressing from bucolic nostalgia to abject melancholy. This is the soundtrack of Caspar David Fredrich’s crumbling Gothic ruins; lamentations for a bygone era unsullied by modernity. The obvious fascistic underpinnings of such are of key focus for the film, which attacks the image of folkloric “Mother Nature” and its residual trace within contemporary gender norms. Christiansen’s deployment of a politically-charged musical form is then to be understood not as naïve reification but ironic pastiche. Consequently, the music itself is subordinate to the broader theoretical aim of the film and not of the same unbridled maverickism marking the composer’s later work, of which only passing glimpses are afforded. One can detect, for instance, in the score’s more tactile moments—when field recordings rest unsettlingly alongside electronics and folksong—foretastes of 1985’s Symphony Natura and even a nascent form of Lambkin’s masterful Salmon Run of 2007. The record, then, is worthwhile to those seeking an understanding of Christiansen’s stylistic development and ties to the radical currents of post-war expression, but otherwise is best experienced within the context of the film, from which it is conceptually inseparable.

Details of Ursula’s 1986 Den Røde Skov (The Red Forest) are scarce. The Danish Film Institute listing points to a theme of mother-daughter relations explored across nine tableaux, continuing the previous film’s problematization of mythic Woman (a premise resting alongside Antouanetta Angelidi’s poetic exegesis of feminine representation Topos, released a year prior). The island of Møn again serves as the site of cinematography, though it now assumes a central importance within the soundtrack.

Coming some 15 years after The Executioner, Den Røde Skov marks a significant progression in Christiansen’s practice. Long departed from a historically-framed aesthetic, the artist has since arrived at his own idiosyncratic juncture resisting classificatory ease. Though musique concrète in technical construction (comprising an assemblage of found sound, manipulated tape tracks, and field recordings), the score is riddled with cultural and locational significations raising it beyond a Schaefferian sound-phenomenology. Nor can Christiansen be firmly located within the field of sound art, for his creations are too authorly to be cast alongside the depersonalized documents of acoustico-spatial phenomena associated with Bill Fontana and Max Eastley. His Fluxus relation may still serve as a provisional point of reference, but he is not set on a self-defeating anti-art. One may instead liken his mature style—neighboring fellow wayfarers of the musical periphery Hans Krüsi, Ghédalia Tazartès, and Basil Kirchin—to an aural art brut (notwithstanding a background in classical training); raw intuition free from generic constraint, marked by the temperament of a wholly singular, heterodox persuasion.

Contrary to the practice of a traditional film score, which resides parallel to cinematic action in a detached correspondence, Den Røde Skov wavers between mimesis and abstraction. The presence of objective sound-markers—waves, birdsong, ocean wind—are quasi-diegetic insofar as they correlate to mise-en-scène yet remain obliquely outside of direct representation due to the estrangement afforded by electronic manipulation. Unusual too is the continuity with which the work unfolds, anathema to the fragmentation typical of narrative films broken up into spatially or temporally distinct scenes. It is, rather, more akin to a migratory drift traversing interconnected regions of sound, after the “radio programme” mode of concrete music taken up in Pierre Henry’s 1968 tour of horror Apocalypse de Jean. A cohesion is maintained within the very scope of the score’s sound-universe such that it assumes a filmic presence in itself, rife with dramatic and perceptual detail. To recall a phrase of Michel Chion, it is “cinema for the ears.”

The diversity of sound present in Den Røde Skov is remarkable. Christiansen refuses to settle his palette within any fixed register; there is an almost carnivalesque quality to the score’s tonal shifts. Industrial dirges befitting Einstürzende Neubauten slip into the pastoral reverie of Wendy Carlos’ Sonic Seasonings while otherworldly, modulated voices attaining the animalism of Luciano Berio’s Visage disrupt subdued field recordings. The score’s contiguity would seemingly be threatened by a turn towards collage, in which decentered juxtaposition takes the fore, were not it grounded by the sustained presence of Møn’s soundscape. Christiansen, however, defies the purity of capture demanded by the program of acoustic ecology associated with soundscape theorist R. Murray Schafer, for whom the practice of locational sound-documentation is bound up with a normative good. In Schafer’s view, field recording is a means of retaining the sonic imprint of an atrophying environment, of sifting out the “sounds that matter”—those coded as natural or bound to communal tradition—while casting aside those which do not. But should this ethic of preservation remain absolute and unquestioned? Within this stance is, arguably, a recourse to the self-same ideal historicism taken up by The Executioner.

Christiansen accords no such transcendent status to any one type of sound; for him, all is but potential material to be actualized. Hence, he intermixes machinic textures with naturalistic, as when he deploys the harsh timbre of a digital telephone ring adjacent to woodwind folk-instrumentation. Nor is the composer satisfied with a neutral in situ portraiture, the “almost nothing” of Luc Ferrari’s quotidian travelogues. Den Røde Skov’s soundscape is rather one in which the real is haunted by the mythological. The score’s second half is dominated by the motif of a wolf’s howl, a recurring device for the composer. Harwood notes in his feature on Christiansen an anecdote shared by a son: “Henning was obsessed with the sound of the wolf, always the howl of the wolf, this striking lone cry.” One then wonders if the omnipresence of this motif throughout his oeuvre does not figure as an exorcism of trauma, à la Robert Ashley’s “working-through” of an involuntary speech disorder in his disturbing Automatic Writing, or a construction of shamanistic mytho-biography after his friend, collaborator and fellow Fluxus eccentric Joseph Beuys. Perhaps the symbol goes beyond the personal. That the creature has been absent from Denmark’s soil for some two centuries would confer onto its howl the distinction of what Schafer calls archetypal: “those mysterious ancient sounds, often possessing felicitous symbolism, which we have inherited from remote antiquity or prehistory." Could then this symbol, so laden with connotations of nationhood and atavistic tribalism, be marshalled to confront the naturalized group-identities figuring so prominently in Ursula Christiansen’s films? In any case, the device with its multiplicity of reference serves as a striking, ever elusive refrain.

Towards the end of the record’s A-side one hears the ringing of distant church-bells. Though their source is undisclosed, these tones likely emanate from Møn’s famous Fanefjord Church, a historical landmark overlooking an inlet of the Baltic Sea. Perched atop a hill and set in stark contrast between its red-tiled roof and whitewashed exterior, it commands the eye from a far distance. Within are frescoes painted by the nameless 16th-century artist designated “the Elmelunde Master”, known only by his distinctive emblem. As the island’s cultural locus, Fanefjord is the apt resting place of Christiansen, buried in its churchyard in 2008. His gravestone is adorned with a large sculpture of an ear, as if to eternalize the composer’s relation to the acoustic surrounding. For this composer, sound was always something subject to ongoing deliberation.